M. Rosalind Morris, University of Nebraska–Lincoln emeritus professor of plant cytogenetics, is internationally recognized for her pioneering work in wheat cytogenetics and in showing the effects of irradiation on corn. Her career at Nebraska spanned from 1947 to 1990.

For more than 30 years, Morris’ research focus was to locate important characteristics in wheat genes that would be useful in breeding wheat varieties. She and her team developed chromosome substitution lines where they would take a chromosome pair from one wheat variety and substitute it into the background of another variety. The varieties had to differ somewhat in some of their characteristics. By putting one chromosome pair into another variety, they could then find out what characteristics that pair was contributing. These substitution lines became very useful worldwide and formed the basis for current research done by P. Stephen Baenziger, professor and Wheat Growers Presidential Chair in Nebraska’s Department of Agronomy and Horticulture.

“She was a gentle scientist who worked tirelessly to create a set of lines that were second to none for studying the agronomic and end-use quality performance of hard winter wheat,” Baenziger said.

Morris was born on May 8, 1920, in Ruthin, North Wales, to schoolteacher parents. Her father survived the 1918 influenza outbreak, but it left him in poor health. At the recommendation of his doctor to seek an outdoor life, the family immigrated to Canada in 1925 and bought a 50-acre fruit farm in southwestern Ontario. Her father’s health quickly improved, and they adapted to the more rustic lifestyle.

Morris attended a one-room country schoolhouse for elementary education. She helped her parents in harvesting fruits and vegetables and with other farm chores. In her teens, she became increasingly interested in agriculture and more involved in the farm operations.

In high school, literature was Morris’s favorite subject, and she considered a career in journalism. She graduated from high school in 1938.

Because of her interest in agriculture and with little money to send her to a prestigious university following the Great Depression, her parents decided she would go to Ontario Agriculture College, now part of the University of Guelph, near Toronto. In 1942, Morris earned a Bachelor of Science and Arts in horticulture at OAC.

She was accepted into the plant breeding graduate program at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and offered a teaching assistantship. At a time when women rarely pursued graduate work in science, Morris was afforded this unique opportunity because most college-age men were involved in World War II. Out of 150 students in her class, five were women. Only she and Leona Schnell received Ph.D.s in plant breeding and genetics from Cornell, the first women to do so.

As a graduate student, Morris initially studied fruit plant breeding but transitioned to the study of crop plants. She assisted her adviser with small-grains research and conducted her own research on buckwheat. However, seeing chromosomes under a microscope in a cytology course captivated her interest and changed her career path. In 1947, Morris accepted an assistant professor position at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, becoming the first woman faculty member hired by the Department of Agronomy and Horticulture.

Her career at Nebraska began with the support of the late Robert Cushing, then an assistant professor of plant breeding at Cornell, whom she had assisted in teaching genetics courses. When he learned that his alma mater, the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, was searching for an assistant professor to work with the late Elvin Frolik on an Atomic Energy Commission grant in a newly created plant cytogenetics program, he enthusiastically recommended Morris.

At first, Nebraska couldn’t hire her because she was not a U.S. citizen and couldn’t be paid by state funds. Through the efforts of Frolik and Franklin Keim, department head at the time, non-state funds were secured to hire her. Eventually Keim and Frolik worked with the legislature to pass a resolution that if they could not find anyone with the same training in this country, then they could go outside the country. Thus, Morris was able to stay.

Still a Canadian citizen, Morris thought she would eventually go back to Canada to be closer to her parents. “But as time went on, I found I was going to settle here,” Morris said. She became a naturalized citizen in 1954.

With Frolik, she studied the cytogenetic effects of atomic irradiation on corn out of concern over the effects of atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. She harvested corn tassels and shipped them in dry ice by air to the Argonne Laboratory near Chicago, where they were exposed to radiation and returned to her for study. They tested different doses and types of radiation and looked for chromosome abnormalities as a result of these radiations. Results showed radiation could break or rearrange chromosomes depending on the dose. It could also reduce corn fertility and seed amounts.

Morris was left in charge of the program soon after arriving in Nebraska when Frolik went to Minnesota to obtain his doctoral degree.

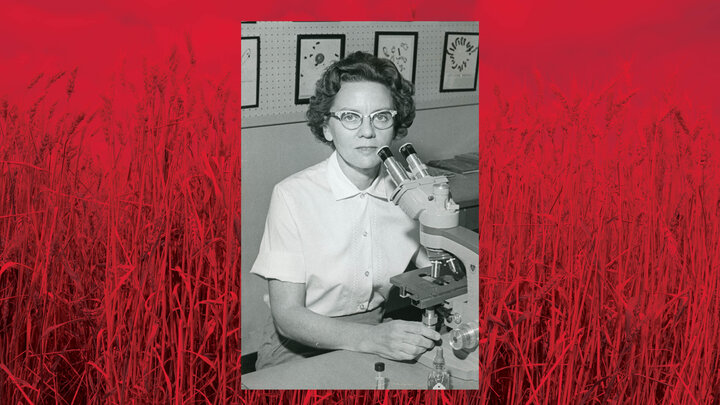

M. Rosalind Morris circa 1962. Photo courtesy of UNL Archives & Special Collections.

M. Rosalind Morris. Photo courtesy of UNL Archives & Special Collections.

In 1949, Morris took a one-year postdoctoral position at California Institute of Technology in Pasadena to further her technical skills in microscopy work and to learn to identify radiation-induced chromosome abnormalities in maize.

When Frolik became head of the department in 1952, Morris, Francis Haskins and Charlie Gardner took over his teaching duties which included statistical genetics, chemical genetics, cytogenetics and plant genetics for graduate students. Morris enjoyed teaching and working with students on writing papers, especially those students from other countries with English as a second language.

Morris was promoted to an associate professor in 1953 and professor in 1958.

In 1956, Morris received the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship and traveled to Sweden and England to continue irradiation studies on crop plants.

“It was a joy for me to sit at the microscope and look for those beautiful chromosome spreads,” Morris said. “My research was based on the misbehavior of chromosomes and it took a lot of patience and persistence. Those studies were a forerunner for molecular research on wheat chromosomes and genes.”

Upon returning to Nebraska, Morris changed her research focus to the cytogenetics of bread wheat and continued to teach until her retirement in 1990. Her research led to the development of new wheat varieties and provided a premier resource base for the emerging field of functional genomics.

M. Rosalind Morris in her office, circa 1964. Photo courtesy of UNL Archives & Special Collections.

M. Rosalind Morris examines her wheat research in the agronomy greenhouse on East Campus, with her dog, circa 1968. Photo courtesy of UNL Archives & Special Collections.

Morris co-authored the book Chromosome Biology, a comprehensive and practical textbook, in 1990.

In 1979, Morris became the first woman honored as a Fellow of the American Society of Agronomy. “I always wonder what it must be like to be honored as the first woman Fellow of the American Society of Agronomy. With her understanding of the English language, I bet it made her smile,” Baenziger said.

Morris also received fellowships to the Crop Science Society of America and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

She served as president of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences in 1980, the first woman in over 50 years.

In addition, she was awarded the following: Noteworthy Cytogeneticist by Marquis Who’s Who; Distinguished Service to Agriculture Award, Gamma Sigma Delta-Nebraska Chapter; Distinguished Scientist Award, Sigma XI Nebraska Chapter; Women of Distinction award, Soroptimist International of Lincoln, Nebraska; President’s Club, University of Nebraska Foundation; Friend of Science Award, Nebraska Academy of Sciences; and Service to Mankind Award, University Sertoma Club.

When asked what career accomplishments gave her the most satisfaction, Morris responded that contact with and imparting knowledge to her students and helping them with writing papers were her teaching successes. In research, it was to have demonstrated the value of combining genetics and cytology.